Capinero Creek in Pixley, CA – Student’s First Field Visit in December 2023

From Dairy to Desert: The Capinero Creek Restoration Story

A data-driven exploration of land transformation in California’s San Joaquin Valley

In the vast expanse of California’s San Joaquin Valley, where endless rows of crops stretch to the horizon and dairy farms dot the landscape like scattered settlements, lies a story of transformation that would capture the attention of scientists across the state. Students from Alpaugh High School took on the challenge of documenting this transformation, embarking on a two-year scientific investigation that would take them from a small valley high school to the state’s premier science competition.

Their project, titled “Restoration of California Dairy Lands at Capinero Creek,” represents rigorous scientific inquiry into one of the most important environmental challenges facing their region—and their findings tell a powerful story.

The Setting: Southwestern Tulare County

The setting is southwestern Tulare County, where the economic realities of modern farming meet the environmental challenges of groundwater depletion. Here, amid this agricultural heartland, the Capinero Creek Restoration Project began as more than just an environmental initiative—it’s a preview of the San Joaquin Valley’s future.

Five hundred acres of former dairy land stretch across the valley floor, marking the site of an ambitious restoration project. The transformation began when the Tule Basin Land & Water Conservation Trust acquired the property with help from a $5 million federal grant, funding from Union Pacific, and California’s Multibenefit Land Repurposing Program. The mission: convert decades of intensive dairy operations back to native alkali scrub habitat for threatened and endangered species.

But this wasn’t just about conservation. With water managers anticipating that at least 70,000 acres will need to be fallowed as the valley reduces groundwater use, Capinero serves as a model for what sustainable land retirement might look like.

The Student Scientists

More than 30 students at Alpaugh High School, developed a comprehensive scientific approach to document the transformation. Their methodology was sophisticated: they would establish baseline data from a healthy ecosystem, measure the extent of degradation at the restoration site, and then track recovery over time.

Establishing the Baseline: Kaweah Blue Oaks Preserve

Before the students could understand the transformation happening at Capinero Creek, they needed to establish what a healthy ecosystem looks like in their region. Their investigation began at the Kaweah Blue Oaks Preserve, a thriving natural area that would serve as a comparison point for measuring restoration success.

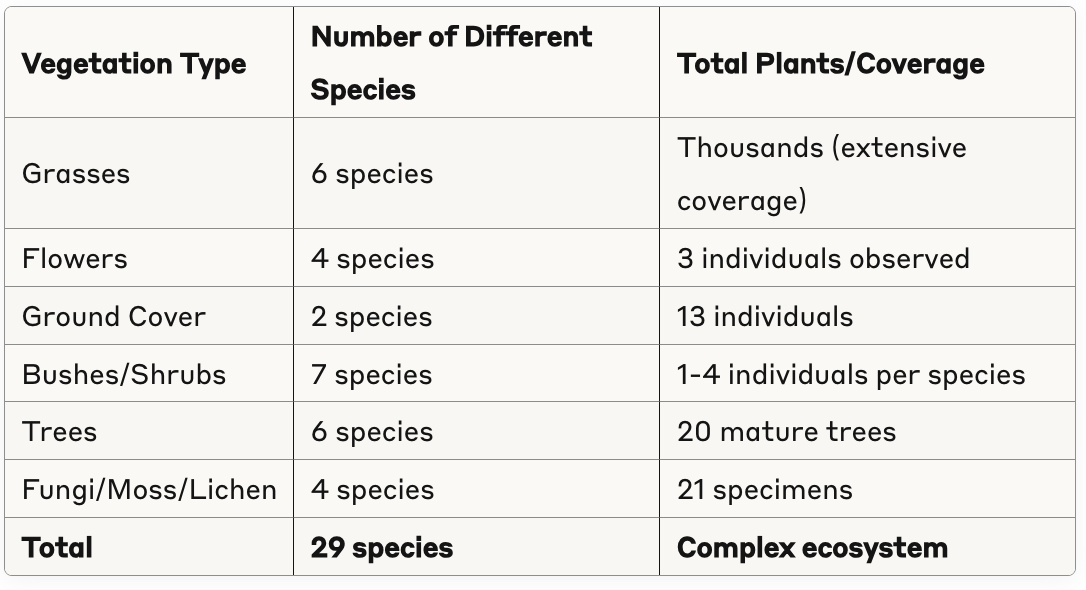

At the preserve, the students documented remarkable diversity using systematic quadrat sampling. Their vegetation surveys revealed a thriving ecosystem:

Blue Oaks Preserve Vegetation Survey Results

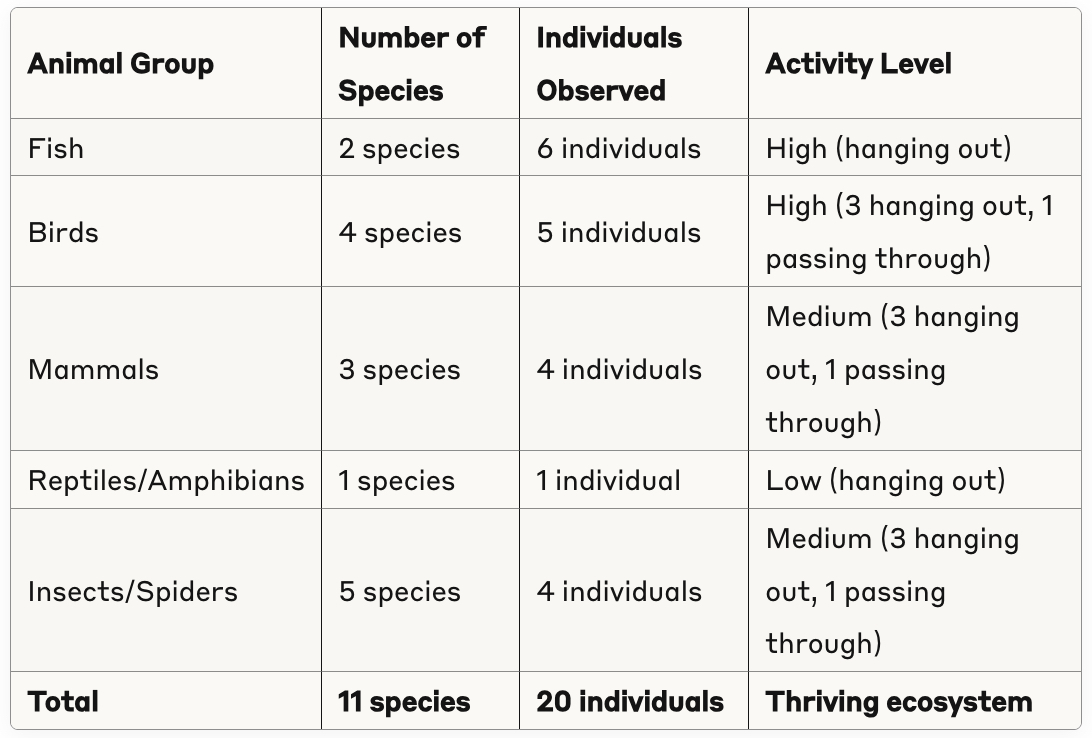

Blue Oaks Preserve Wildlife Survey Results

Perhaps most telling were the abundant signs of wildlife activity scattered throughout the preserve: 8 scattered nests, 4 different types of animal tracks, 3 scat deposits, 4 chewed acorns, and various bones and feathers indicating natural predator-prey relationships.

This baseline data from Blue Oaks would prove crucial for understanding what successful restoration might look like at Capinero Creek.

The Stark Reality: First Encounters with Degraded Land

When the students first visited the Capinero site, they encountered a landscape that told a sobering story of environmental degradation. The contrast with the thriving Blue Oaks Preserve could not have been more dramatic.

“Like mentioned before the arrival of Capinero Creek, it was a dead land. Rarely you would see plants there and on top of that, they were dead and looked like they been dead for some time.”

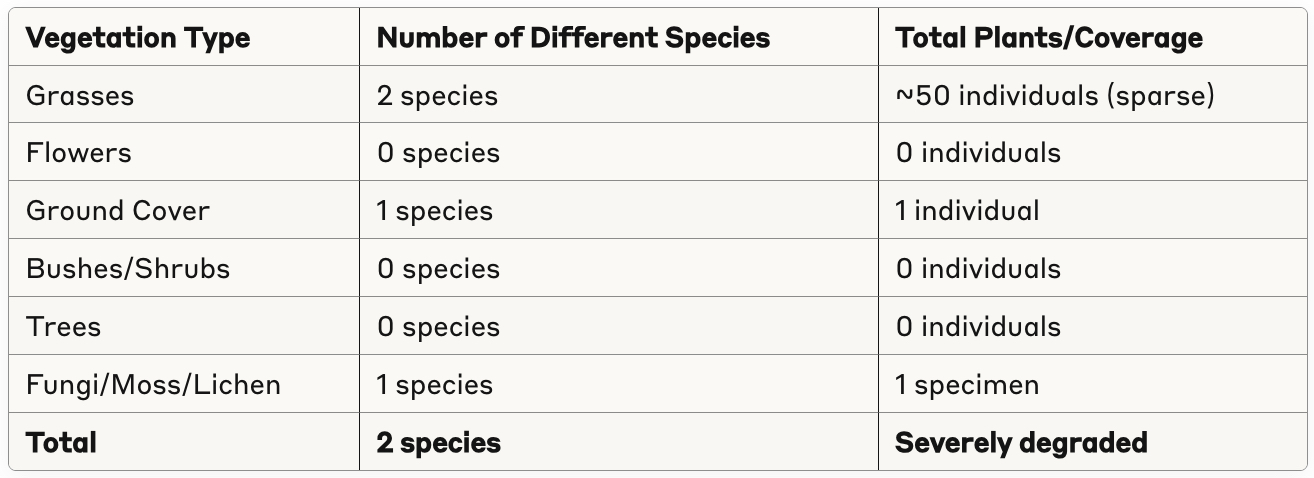

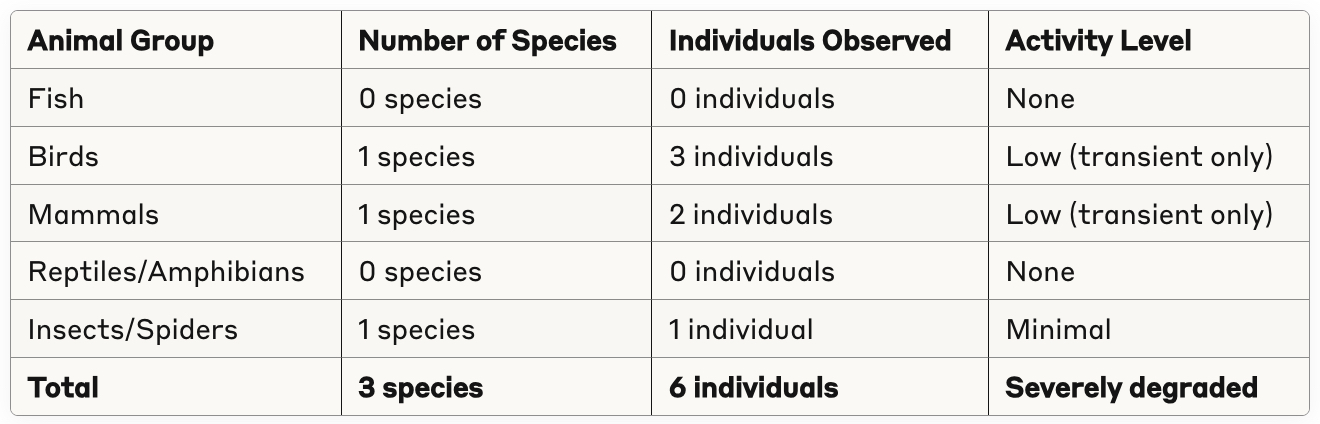

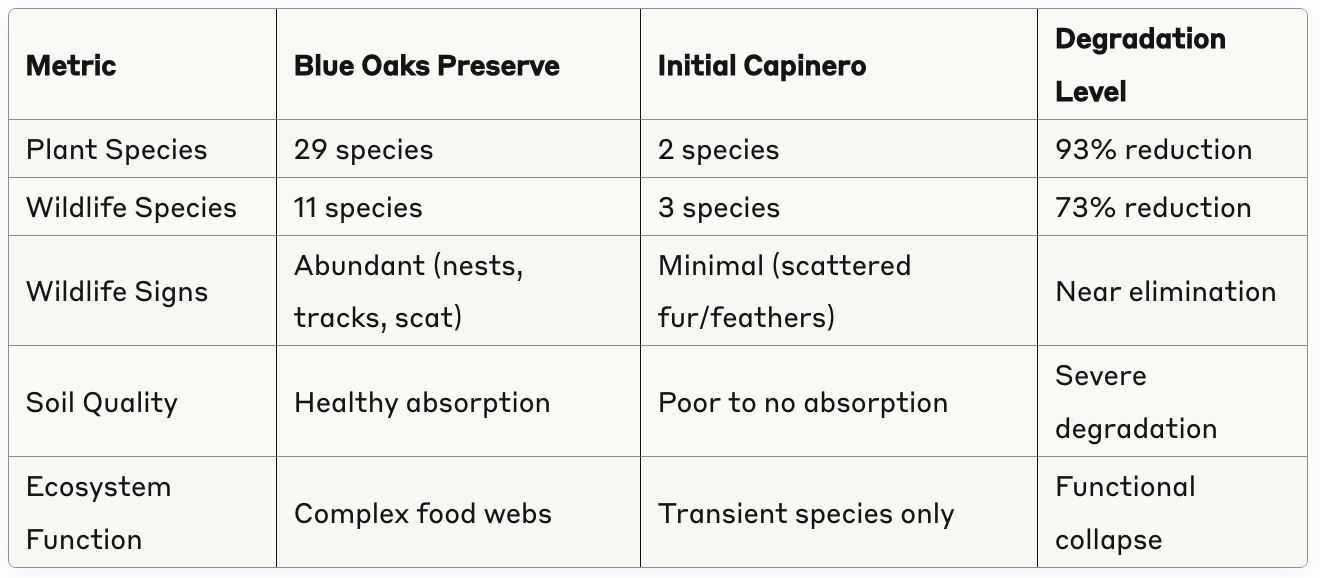

The initial surveys at Capinero revealed an ecosystem in crisis. The stark contrast with Blue Oaks becomes clear when comparing the data:

Student recording data from their quadrat.

Students setting up their quadrat for data collection.

Initial Capinero Site Vegetation Survey Results

Initial Capinero Wildlife Survey Results

Soil Quality Assessment at Initial Capinero Site

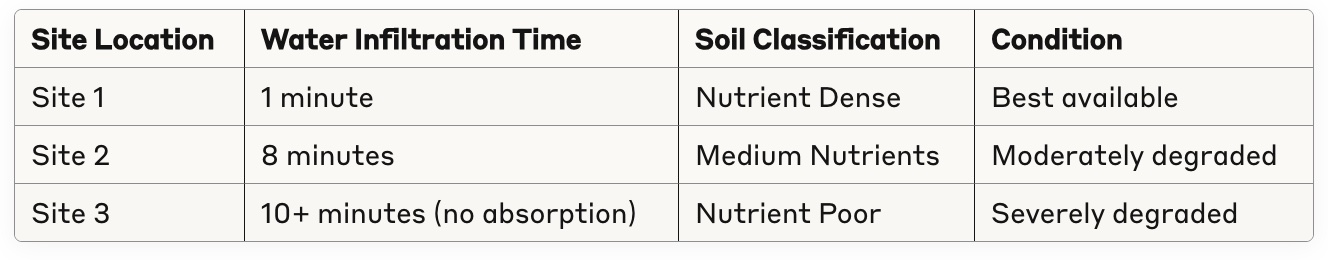

The students conducted soil infiltration tests to understand the degradation:

Site 1 was outside of the observation plot where students observed dense grass growth.

Comparative Analysis: Blue Oaks vs. Initial Capinero

The students’ observations revealed the limited nature of wildlife activity. They found scattered feathers from passing birds, some coyote and rabbit fur caught on sparse vegetation, and a single instance of chewed insects in a ground hole. There were no nests, no scat deposits, no tracks—none of the abundant wildlife signs that characterized the healthy Blue Oaks ecosystem.

a ground hole. There were no nests, no scat deposits, no tracks—none of the abundant wildlife signs that characterized the healthy Blue Oaks ecosystem.

Yet the students recognized both the devastation and the potential.

“Because of the little life left, this is pretty promising for restoration of the land. It can be possible to restore Capinero Creek with the right tools and information to bring back life to the land.”

The Science of Restoration

Armed with their baseline understanding from Blue Oaks and their documentation of degradation at Capinero, the students began tracking the restoration process. Over two years, they conducted systematic research analyzing the transformation of the former dairy land, developing comprehensive methodologies to measure soil health, water quality, air quality, and biodiversity across four distinct quadrants of the restoration area.

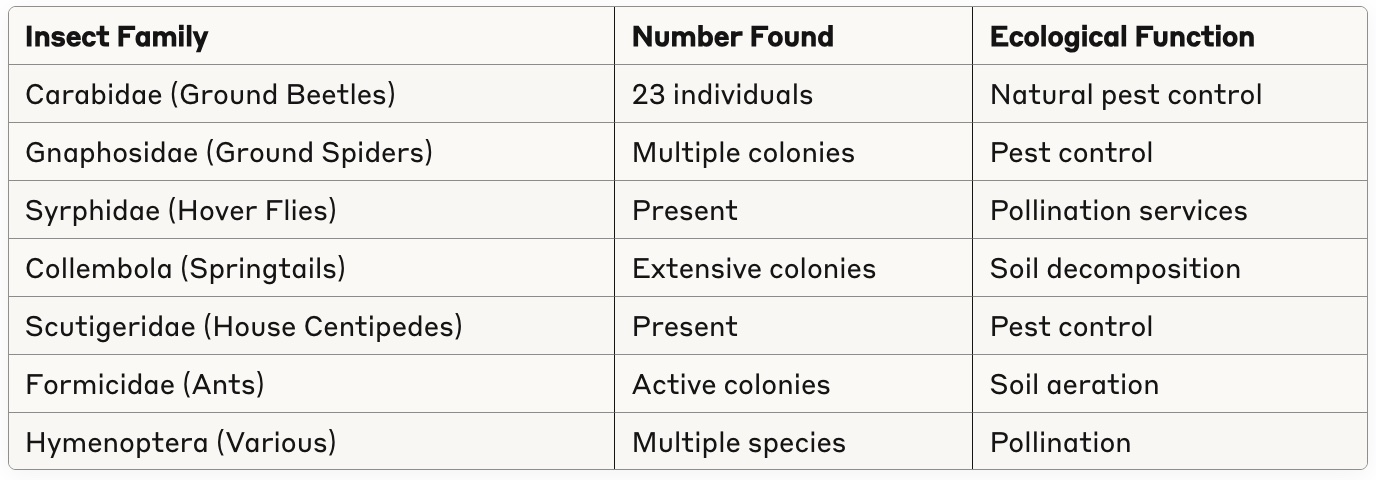

Their research included detailed biodiversity surveys conducted on multiple dates, including November 5, 2024, and January 16, 2025, using standardized sweep net sampling techniques to document insect and arachnid populations as indicators of ecosystem health.

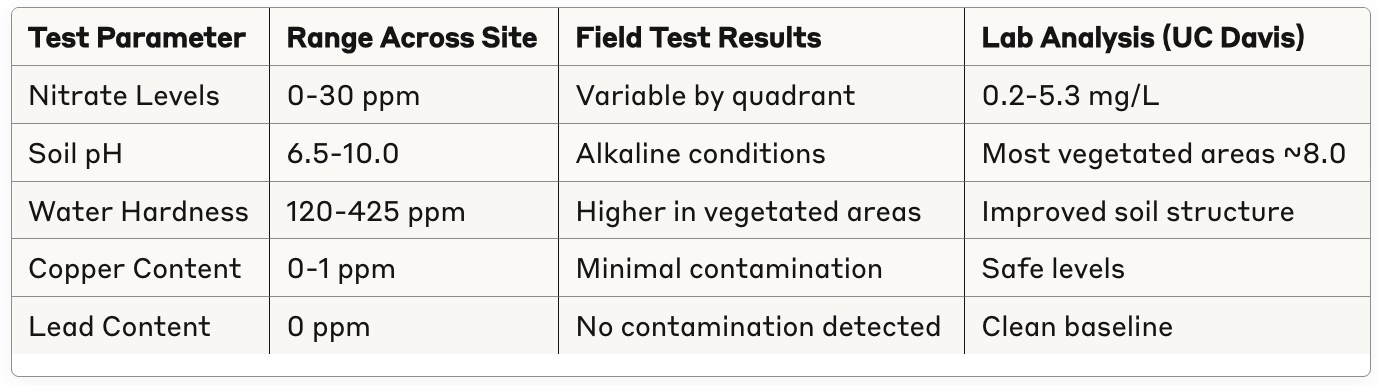

Soil Chemistry Analysis

The students collected soil samples from different microhabitats within each quadrant, using colored flags to mark specific zones: white flags for bare soil areas, green flags for areas with vegetation structure, red flags for areas with vegetation plus organic material, and blue flags for areas with vegetation structure, red flags for areas with vegetation plus organic material, and blue flags for areas with vegetation, organic material, and rocks/logs.

Insect and Arachnid Biodiversity Assessment

The students’ biodiversity data revealed beneficial species beginning to colonize the restoration site:

Capinero Restoration Beneficial Insect Survey Results

Recognition and Achievement

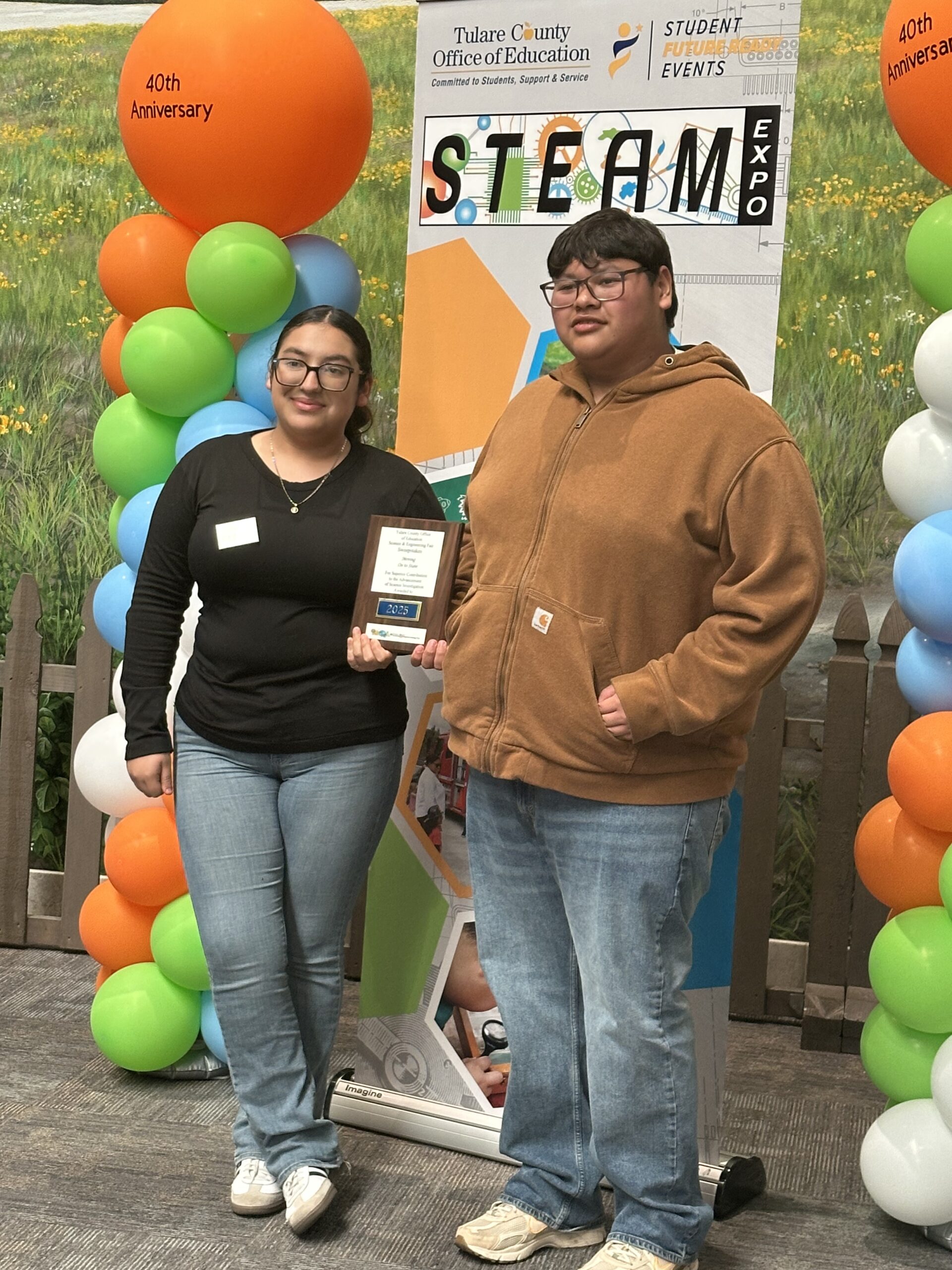

The students’ rigorous scientific work earned them recognition at the highest levels. Their project first won the Tulare County Office of Education Science and Engineering Fair in March 2025, qualifying them for the prestigious California Science and Engineering Fair in April 2025.

At the state competition held at California Lutheran University in Thousand Oaks, Edwin Marquez and Estrella Chaidez competed against more than 800 students from 351 schools across California in the Earth and Environment category. Their presentation on the Capinero restoration project earned them second place in the statewide competition—a remarkable achievement that brought recognition to their innovative research approach of using reference sites to measure restoration success.

The Continuing Story

As the restoration site continues to evolve, the data collected by these young scientists provides a foundation for understanding long-term ecological recovery. The students’ research documents a remarkable transformation arc: from the thriving 29-species plant community at Blue Oaks, to the devastated 2-species wasteland they first encountered at Capinero, to the emerging beneficial insect communities that began establishing during the restoration process.

The comparison across all three phases shows both the devastating impact of intensive agriculture and the potential for recovery. The reference site’s 29 plant species and 11 wildlife species represent a target for long-term restoration success, while the initial 2 plant species and 3 wildlife species at Capinero show just how degraded the land had become. The emerging beneficial insect communities during restoration suggest the site is on a positive trajectory toward that goal.

The students’ achievement demonstrates that important environmental research is happening in communities across the valley. These young scientists are not just documenting change; they’re helping to shape how their communities understand and adapt to the challenges ahead by establishing scientific baselines, measuring the extent of degradation, and tracking progress toward recovery using clear reference points.

The story of Capinero Creek is ultimately a story about scientific inquiry, environmental stewardship, and the power of rigorous research to document and understand landscape transformation. As the San Joaquin Valley continues to grapple with water scarcity, climate change, and agricultural adaptation, projects like Capinero—supported by careful baseline studies and honest documentation of environmental degradation—offer evidence-based insights into how change can be both necessary and beneficial.

From dairy to desert, from devastation to recovery, from reference site to restoration site—the Capinero story continues to unfold, one data point and one discovery at a time.

Acknowledgements

The Capinero Creek Restoration Project is managed by Tule Basin Land & Water Conservation Trust and The Nature Conservancy in partnership with River Partners. Funding from Union Pacific Railroad made this educational project possible. For more information about land repurposing projects in the San Joaquin Valley, visit https://tule-mlrp.org

Our Partners:

Alpaugh High School